In a new survey, a majority of respondents support the expansion of families’ education options. But specific programs such as vouchers remain polarizing.

The results of a new poll suggest that a majority of Americans now support the expansion of school choice for all families. With 54 percent of respondents saying they favor universal-choice policies—which typically come in the form of programs that let families use government money to pay for private schools—the findings released on Tuesday by the policy and opinion magazine Education Next indicate that the idea has enjoyed a substantial jump in popularity since last year, when just 45 percent of respondents said they supported such proposals.

These findings are a boon for the Trump administration, which has advocated for school choice from the get-go to little avail, with Congress ignoring his 2017 budget plan calling on the federal government to dedicate $1.4 billion to expanding vouchers and again rejecting a similar proposal this year. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos previously served as the board chairwoman of the American Federation for Children, which describes itself as “the nation’s voice for educational choice”; when announcing DeVos’s appointment, Trump indicated he selected her precisely to help advance his school-choice agenda.

It’s not clear whether the administration’s public support for school-choice policies is driving the apparent shift in public opinion. But it’s curious, considering that DeVos, the most high-profile cheerleader for school choice, is also Trump’s least-popular cabinet member. In a March 2018 poll, 28 percent of respondents said they have a “very unfavorable” impression of DeVos, while just 8 percent found her “very favorable.” But at least according to these numbers, her reputation doesn’t seem to be hurting public support for school choice. That’s especially evident among Republicans, who have in recent years grown to espouse school choice as a key component of the party’s platform. And in this survey, 64 percent of Republican respondents said they support school choice for all families, a 10-percentage-point increase from last year. Fewer than half—47 percent—of Democrats said they’d favor such a proposal, up 7 percentage points from the 2017 poll.

DeVos’s press secretary began promoting the Education Next results on Twitter as soon as they were released. In one tweet, she cited an analysis of the poll by the K-12 expert Frederick Hess, of the right-leaning American Enterprise Institute: “public strongly prefers Betsy DeVos’s ‘extremist’ views.” It was the first time she’d tweeted in weeks.

The poll surveyed a nationally representative sample of roughly 4,600 adults this past May. Notably, the survey included oversamples of parents with school-age children living in their home, teachers, African Americans, and Hispanics. Also notable: While Education Next, which was founded in 2001 by a school-choice-focused task force based out of Stanford’s Hoover Institution, states on its website that it “partakes of no program, campaign, or ideology,” many education insiders describe it as partial toward “free-market education-reform ideas” like charters and vouchers.

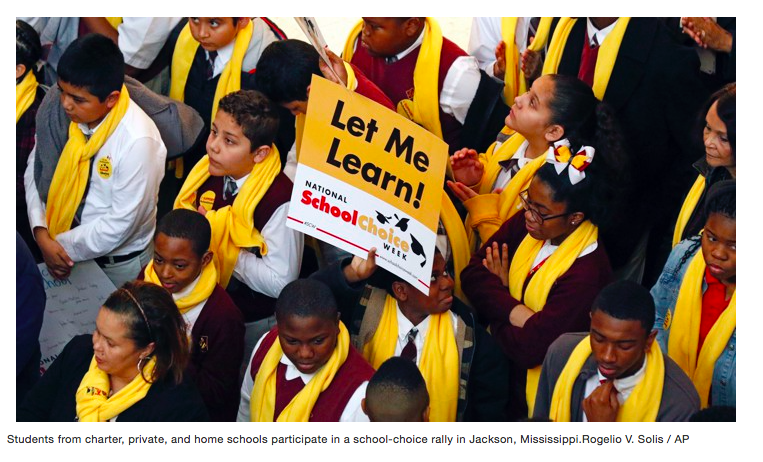

But Americans’ support for these programs changes depending on how they’re presented. Fifty-four percent of respondents said they were in favor of universal vouchers only when asked about a proposal that “would give all families with children in public schools a wider choice, by allowing them to enroll their children in private schools instead, with government helping to pay the tuition.” The word “vouchers” wasn’t included. But among respondents who were asked explicitly about vouchers, support dropped to 44 percent. Previous research has suggested that people are less likely to support the use of public money for private-school tuition when it’s described explicitly as a “voucher” program. As Chalkbeat’s Matt Barnum writes, such inconsistencies are common in surveys that ask laypeople about vouchers because the polarization surrounding the topic means that even a small semantic nuance can affect a person’s perception. The issue has become so politicized that advocates of such programs often avoid the word “voucher” altogether—National School Choice Week, for example doesn’t use the word on its website, instead using the euphemistic “opportunity scholarships”—a strategy that aligns with advice often disseminated by Republican pollsters.

Interestingly, when it came to respondents’ opinions on vouchers earmarked only for low-income students, whether the question included the word “vouchers” made little difference: The percent in support for low-income voucher programs hovered around the mid-40s for each phrasing.

But the role of semantics in shaping public opinion on vouchers is clear, echoing a broader trend in education rhetoric. Even the term “school choice” has become loaded—so much that even DeVos has started to shy away from it. In a February analysis, Politico’s Kimberly Hefling and Caitlin Emma highlighted the secretary’s tendency toward more politically palatable phrases instead—things like “innovation” and “blended learning” and “a paradigm shift.”

Charter schools are perhaps the most well-known “school choice” model. Since many people are generally familiar with how charters work, the term isn’t as susceptible to spin, which could mean polling on this front is a more authentic barometer for shifting opinions on school-choice issues. Close to half—44 percent—of respondents in the Education Next poll this year said they support the formation of “charter schools,” a term defined in the question as meaning “publicly funded but … not managed by the local school board.” That’s up from 39 percent in 2017—a year marked by a drastic decline in public support for the model—which may help convince skeptics that Americans are truly, albeit gradually, buying more and more into school choice.

Then again: Those opposed to school-choice policies might take issue with the wording in that question, too. Describing them as “not managed by the local school board” sounds a lot more appealing than directly noting that they’re managed by private entities, including both nonprofit and for-profit organizations. That’s particularly true in an era when “privatization” is practically a taboo word for many in the education world. But however carefully these models are described, they’ll still carry polarizing subtext. It’s almost impossible to completely take politics out of schools.

— Alia Wong is a staff writer at The Atlantic, where she covers education and families.